What is an Atrioventricular Septal Defect or an AV Canal Defect?

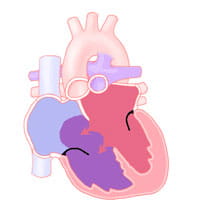

Atrioventricular septal defects (AVSD) are a common group of congenital heart defects.

Atrioventricular septal defects make up about 5% of all congenital heart disease. They are most common in infants with Down syndrome.

The main defect is that part of the heart called the endocardial cushions does not form properly during heart development before birth. The endocardial cushions separate the parts of the heart.

The endocardial cushions help form part of the atrial septum (the wall that divides the right atrium from the left atrium). The ventricular septum (the wall that divides the right ventricle from the left ventricle) is also made from the endocardial cushions.

The endocardial cushions also separate the right- and left-sided valves. An atrioventricular septal defect can include the heart not having any of these structures formed.

AVSD Categories

Atrioventricular septal defects can be put into one of three categories; complete, partial (or incomplete), or transitional.

A complete atrioventricular septal defect is one in which there are defects in all structures made by the endocardial cushions. There are defects (holes) in the walls between the right and left atrium and ventricle. The atrioventricular (AV) valve stays undivided into right and left or "common."

A partial or incomplete atrioventricular septal defect is one in which the part of the ventricular septum made by the endocardial cushions has filled in. There are separate right- and left-sided valves are two different valves. In this case, the defect is in the atrial septum and left-sided valve. This type of atrial septal defect is called an ostium primum atrial septal defect. The left sided valve has a cleft (incomplete formation of one of its leaflets), causing the valve to leak.

The transitional type of defect can look like the complete form of atrioventricular septal defect but the leaflets of the AV valve are stuck stuck to the ventricular septum. This divides the valve into two valves and mostly closes the hole between the ventricles.

As a result of the small defect between the ventricles, a transitional atrioventricular septal defect causes symptoms similar to a partial atrioventricular septal defect.

Atrioventricular septal defect is a common part of more complex heart disease that occurs in heterotaxy syndromes (when the heart and other organs are in the wrong place in the chest and abdomen). There are also forms of atrioventricular septal defects that lead to the common AV valve opening into one of the ventricles. The other ventricle is underdeveloped. An atrioventricular septal defect can also include the heart not having certain structures formed or being much smaller than normal. These situations are better described as single ventricle lesions such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome or tricuspid atresia.

Atrioventricular septal defects can occur with other types of congenital heart disease such as coarctation of the aorta or tetralogy of Fallot.

Problems With AVSD

A complete atrioventricular septal defect allows blood that has picked up oxygen in the lungs to cross the atrial and ventricular septum from the left side to the right side of the heart. The blood then goes back out the pulmonary artery to the lungs.

This re-circulation of extra blood to the lungs is called a left-to-right shunt. The left ventricle must pump already oxygenated blood back to the lungs. At the same time, the left ventricle is trying to meet the body's usual demand for its own oxygenated blood.

The amount of extra blood pumped by the left ventricle is often two to three times more than what is pumped by the left ventricle in a normal heart.

Because there is a large hole in the ventricular septum, the high pressure normally created by the left ventricle to send blood throughout the body is also sent to the lungs. Having a large left-to-right shunt, the higher workload on the left ventricle and the high pulmonary artery pressure causes the lungs to be filled with more blood than normal. This causes fluid to leak from the bloodstream into the air spaces of the lungs. This condition is called pulmonary edema. Pulmonary edema makes it harder for a baby to breathe comfortably. The combination of increased heart and lung work uses large amounts of energy. This results in congestive heart failure (CHF).

Signs and Symptoms of AVSD

The specific type of defect impacts the symptoms that may develop. It also impacts the timing and details of surgical repair.

Babies with congestive heart failure breathe fast and hard. They often sweat and / or tire out while feeding. They also grow slowly or lose weight. These symptoms develop slowly over the first one to two months of life.

The doctor will hear a heart murmur when this type of defect is present. The murmur is caused by the blood passing from the left ventricle to the right ventricle and out the pulmonary artery. They will also note how fast the baby is breathing and if they are using extra muscles to breathe harder.

A small number of infants with a complete atrioventricular septal defect will not develop congestive heart failure. This occurs because the muscle cells that line the small arteries in the lungs get bigger and tighter to protect the lungs from the extra flow and high pressure from the atrioventricular septal defect.

This is called increased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), or pulmonary vascular disease. This condition is more common in infants with Down syndrome.

When there is an increase in pulmonary vascular resistance, the baby may not develop the signs and symptoms of congestive heart failure since the pulmonary vascular resistance reduces the amount of left-to-right shunt. It may cause blood with low oxygen to go the opposite way (from the right ventricle to the left ventricle) and out to the body without picking up oxygen in the lungs.

The oxygen saturation in the body will then be lower than normal, causing cyanosis, which is a bluish discoloration of the skin, fingernails and mouth. It may also cause the murmur to be softer.

Infants with a complete atrioventricular septal defect and elevated pulmonary vascular resistance often grow better and look healthier than those with low pulmonary vascular resistance and congestive heart failure. However, there is a risk of permanent changes to the pulmonary arteries that will not allow them to relax to normal even after surgery to repair the defect. Therefore, having high pulmonary vascular resistance may prompt early surgical correction of the defect.

Repair of the atrioventricular septal defect lowers the pressure in the pulmonary artery. It allows the arteries to relax before they become permanently narrow.

Infants with the partial or transitional forms of atrioventricular septal defects have noticeable signs and symptoms. since the hole between the ventricles is small or not present at all. However, they still have more blood going through the pulmonary artery than normal. There is more work on the heart. Growth may occur more slowly than in infants and children with normal hearts. There is a heart murmur present and it is softer than a murmur with a complete atrioventricular septal defect.

Since there are fewer symptoms, partial or transitional atrioventricular septal defects may not come to medical attention until the child is several months or even years old.

Congestive heart failure, growth failure or a very loud murmur in a child with a partial atrioventricular septal defect can occur when the defect in the left-sided valve leaflet causes this valve to be very leaky and causes extra work for the left ventricle.

Diagnosis of AVSD

A heart murmur is often the first clue that this heart defect exists. It is noted in the first week or two of life. It is common that no murmur is present at birth.

The diagnosis of atrioventricular septal defect in any form is made by echocardiography. A chest X-ray and an electrocardiogram may be used to help with the assessment.

This heart defect may be diagnosed on fetal echocardiograms. It is one of the cardiac defects that may be found on screening ultrasounds at the obstetrician's office. Early diagnosis of the defect allows for prompt intervention at the time of birth if needed.

Planning to deliver an infant at a hospital capable of newborn resuscitation is important in improving care and confirming diagnosis.

Echocardiograms can give detailed information of the specific anatomy of the various cardiac structures affected in this congenital defect. They also give important information about the function of the heart.

There is a high chance of atrioventricular septal defects in infants with Down syndrome. All infants with Down syndrome should have an echocardiogram. This should happen even if there is not a heart murmur or if the child doesn’t have any signs or symptoms.

Treatment for AVSD

Infants with symptoms of atrioventricular septal defects may have improvement in their symptoms with medicine. In all cases, corrective heart surgery will be needed.

Medicines used to treat congestive heart failure from left-to-right shunts in infants include diuretics (helping to rid the body of extra sodium and water) such as Lasix (furosemide).

Medical treatment of infants with atrioventricular septal defects relieves symptoms. It also allows the baby to get big enough to have surgery with lower risks. They may require increased calories by fortification of breast milk or formula to help gain weight.

Surgery typically occurs at 3-6 months for infants with a complete atrioventricular septal defect. Surgery happens around 6-18 months for infants with a partial atrioventricular septal defect.

Surgical repair of either type of defect involves closing of the holes with a patch. It also includes reconstruction of the common atrioventricular valve.

Complications after surgery can happen if the opening in the valves (more commonly the left-sided valve) is too narrow or very leaky.

Additionally, the tissue that transmits the impulse for the heart between the atrium and ventricles runs near the area where the stitches for the ventricular patch need to be placed. If this impulse is interrupted, a pacemaker may be needed.

Atrioventricular Septal Defects Treatment Outcomes

The recovery period after repair of a partial or transitional atrioventricular septal defect is usually short. Most patients are out of the intensive care unit (ICU) in one to two days. They are home in four to five days after surgery.

Reported surgical survival is greater than 97% but is close to 100%.

Repair of a complete atrioventricular septal defect is often complex. It may be associated with other factors that can make recovery after surgery longer.

For example, having higher pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) before surgery can lead to a long time on a mechanical ventilator. The child may need additional medicines to help the heart work well after surgery.

Most patients need two to four days in the intensive care unit after repair of a complete atrioventricular septal defect. They will stay in the hospital for five to seven days after surgery. Survival is 97% for this type of surgery.

Problems with the left-sided (mitral) valve being leaky, the path out of the left ventricle being narrow, or issues with the electrical system of the heart are more common after this type of surgery. The most common problem that is seen after surgery is a leaky left-sided valve. This may need another surgery in 10% of patients. However, after surgery most become medicine-free and free of heart symptoms.

Follow-up visits with the cardiologist are important throughout the child's life to look at valve and heart muscle function. Antibiotic prophylaxis for endocarditis is recommended if there are any remaining holes or significant valve leakage.