What Is Hirschsprung’s Disease?

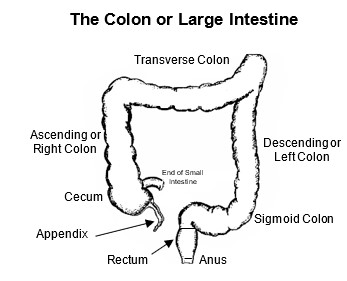

Hirschsprung’s disease (aganglionic megacolon) is a benign congenital (present at birth) condition that affects how the lower intestine works. The lowest parts of the intestine are the colon, rectum and anus (see figure). When we eat, food leaves the stomach, and whatever isn’t absorbed travels through the small intestine and empties into the colon. The waste material slowly moves through the colon and sits in the rectum. Here, it forms into solid stool that can eventually be pushed out as a bowel movement (poop).

Our colon moves the waste material forward because the colon also functions as a pump. It pushes poop forward by squeezing and relaxing, again and again. This pumping function is controlled by two systems of nerves. One controls the squeezing and another controls the relaxing. In Hirschsprung’s disease, the system of nerves that relaxes the colon is missing in a specific part. The missing part is usually the lowest part called the sigmoid colon and rectum. In rare situations, it can involve longer segments and sometimes even the entire colon. When a part of the colon is missing the nerves that relax, that part is always squeezing. This acts like a blockage (obstruction). The child’s belly then becomes full of gas and poop, and they are very uncomfortable. They will have poor appetite and they won’t eat well and grow like babies should. Most of the time this is recognized shortly after birth. But, on rare occasions a child is able to do well enough for it to be missed in the newborn period.

Why Does My Child Have Hirschsprung’s Disease?

The cause of Hirschsprung’s disease is unclear. There is nothing a parent can do that causes the disease. In most cases, the disease results from an abnormality in the genes. The cause of those abnormalities is not known.

Hirschsprung’s disease occurs in about 1 out of 5,000 live births. It is three times more common in males than females. About 5% of cases are linked to Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome). About 2% of cases are linked to Mowat-Wilson syndrome.

Most people with Hirschsprung’s disease do not have a family history of the disease. But, if one parent has Hirschsprung’s disease, there is about a 1% chance their child will have it too. If a couple has a child with Hirschsprung’s disease, there is about a 5% chance that a sibling will be born with it. If a parent or child has long-segment Hirschsprung’s disease, the chances a sibling will be born with Hirschsprung’s disease are higher than if the parent or child has short-segment Hirschsprung’s disease.

Hirschsprung’s Disease Symptoms

Most children with Hirschsprung’s disease show symptoms in the first several weeks of life. Symptoms are most often seen during the first 24 to 48 hours of life. The most common symptoms in this time frame include:

- Not having a bowel movement (pooping)

- Bloating of the belly

- Throwing up

- Difficulty feeding

Sometimes symptoms are not noticed for many months or even years, but this is less common now than it was many years ago.

Children with Hirschsprung’s disease are at a higher risk for an infection called enterocolitis that can cause serious problems. Often called Hirschsprung’s associated enterocolitis (HAEC), this condition is like a gastrointestinal flu. It is characterized by abdominal bloating, foul smelling diarrhea, fever, weakness, fatigue and not feeding well. It rarely occurs in older children and adults. It is most common in newborns and during the first five years of life.

Diagnosing Hirschsprung’s Disease

A physical exam and testing will be done to diagnose Hirschsprung’s disease. Testing includes:

- Abdominal X-ray: An X-ray of the belly may show a bowel blockage (obstruction) or signs of severe constipation. This test is usually the first test that is done. It cannot give an exact diagnosis of Hirschsprung’s disease.

- Contrast enema: This test is done in the radiology department. It allows a special solution to light up on X-ray. This shows the size, shape and position of the colon. This can help estimate how much of the large intestine has been affected.

- Rectal biopsy: This is the most important test. It is the only one that can make the diagnosis of Hirschsprung’s disease. It involves taking a sample of the cells in the rectum for a pathologist to view under a microscope. The pathologist confirms that a child has Hirschsprung’s disease based on the lack of ganglion cells and other abnormal nerve-related findings (such as nerve bundle hypertrophy, calretinin staining, acetylcholinesterase and choline transport). These special tests, in addition to identifying ganglion cells, help determine if a child has Hirschsprung’s disease.

- Suction rectal biopsy: In infants, this test can be done at the bedside in the hospital room without anesthesia. There are very few sensory nerves at the biopsy site, so the procedure is not painful. If the suction biopsy result is inconclusive or if the child is older, a surgical biopsy is done under general anesthesia in the operating room.

- Anal manometry: This test measures anal pressure. It checks the reflexes of the rectum and the anus. This test can be done at the bedside in the hospital room. If your child has a manometry test result that seems to suggest Hirschsprung’s disease, a biopsy should be done to be sure of the diagnosis.

Hirschsprung’s Disease Treatment

Each child with Hirschsprung’s disease has unique needs. The care team will make a treatment plan for your child’s condition and overall health. Based on your child’s needs and stage of treatment, the care team may include:

- Specialized pediatric colorectal surgeon and nurse

- Pediatric gastroenterologist specializing in motility (motion of the digestive system)

- Registered dietician

- Pelvic floor physical therapist

- Psychologist

- Social worker

- Child life specialist

- Other experts as needed

Surgery

Almost all children with Hirschsprung’s disease need a surgery called a pull- through procedure. This involves taking out the diseased part of colon and rectum. Then the end of the colon above the diseased part is pulled down and connected to the anus.

Most often this surgery is done in one step in a minimally invasive laparoscopic way. This means less pain, less blood loss, smaller scars with faster healing and shorter hospital stays. In rare cases, a child may not be well enough to undergo a pull-through procedure in the newborn period. In these cases, the surgeon will bring out the end of the intestine above the affected segment, called an ostomy. This allows the child to pass stool without difficulty. The child will grow and heal until they are well enough to have additional surgery to close the ostomy and have the pull-through procedure.

In situations where the entire colon is affected, an ostomy will be created as the first step. A pull-through procedure will be done after the child is at least 1 year old.

Irrigation

Children with Hirschsprung’s disease will need rectal irrigations when they are first diagnosed to help prevent enterocolitis. Irrigations will remove trapped stool (poop) and gas. Parents and caregivers will be taught to do rectal irrigations, as they may be needed after surgery to treat enterocolitis.

Long-Term Outlook for Children with Hirschsprung’s Disease

Children who have surgery for Hirschsprung’s disease can have excellent quality of life and normal bowel function. When the affected segment has been removed and normal intestine has been connected to the bottom, the intestine may not work as usual. Your child’s bowels may move slower than expected. It is very common for children after Hirschsprung’s surgery to have constipation and other problems such as bloating or soiling. In rare cases, these problems can be significant. When they are, we recommend a comprehensive evaluation to make sure the surgery was done appropriately and that no other problems remain.

There are children who have surgery for Hirschsprung’s disease and have long-term issues after surgery such as bloating and soiling. A biopsy of the pulled-through bowel may be done. Hirschsprung’s disease may be present in the ”normal” bowel. This is called a transition zone pull through. It may occur in about 10% of cases.

After surgery, children are still at risk for enterocolitis. But, with successful surgery and long-term specialized follow-up care, most children can achieve normal bowel habits and an excellent quality of life.

Controversies and Challenges

There are some cases in which a child may be considered to have ”ultra-short” Hirschsprung’s disease. This is a controversial diagnosis as there is no accepted definition of what makes the disease ”ultra-short.” The term ”short” would imply that the affected segment is not as long as most other cases. Some surgeons use the term for a child who has a positive manometry finding (absent recto-anal inhibitory reflex, called a RAIR) but the biopsy result showed ganglion cells. While this is a reasonable definition, it does not necessarily lead to a clear recommendation for treatment. If the ganglion cells are present, there’s no clear segment of Hirschsprung’s disease to remove. Because of this, we avoid using the term, but we understand others may use it.

Another controversial subject is acquired aganglionosis where a child has a biopsy that initially shows normal ganglion cells. Over time, a repeat biopsy shows no ganglion cells. This can be related to what’s called “skip area aganglionosis” in which the segment of Hirschsprung’s disease has areas of normal colon mixed in with the affected colon. These cases are rare and are handled on a case-by-case basis.