What is Ebstein Anomaly?

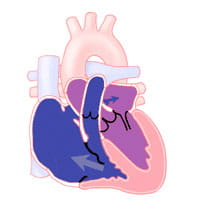

Ebstein anomaly is a defect of the tricuspid valve. The tricuspid valve separates the right atrium (the chamber that receives blood from the body) from the right ventricle (the chamber that pumps blood to the lungs).

Ebstein anomaly is a defect of the tricuspid valve. The tricuspid valve separates the right atrium (the chamber that receives blood from the body) from the right ventricle (the chamber that pumps blood to the lungs).

In Ebstein anomaly, two leaflets of the tricuspid valve are not in the right place. The third leaflet is longer than normal. It may be tied to the wall of the ventricle. Rarely, the valve is so deformed that it will not allow blood to flow easily in the normal direction (right atrium to right ventricle).

Depending on how abnormal the tricuspid valve is, it can allow blood to leak back into the right atrium when the right ventricle contracts (squeezes). As a result, the right atrium becomes larger than normal. If the tricuspid regurgitation (leak) is severe enough, congestive heart failure can result.

If there is a lot of blood flowing back into the right atrium, the pressure within the right atrium becomes very high. Normally, a fetus has a hole between the right and left atrium known as the foramen ovale, which usually closes after birth.

In Ebstein anomaly, the high pressure in the right atrium keeps the foramen ovale open, called a patent foramen ovale (PFO). This connection allows unoxygenated ("blue") blood to flow from the right atrium to the left atrium. The blood goes past the lungs and goes directly to the body. This will result in lower oxygen levels in the blood. This is why children with Ebstein anomaly may look blue or "cyanotic" because they have low oxygen saturations.

Ebstein anomaly may occur with other heart defects, such as pulmonary valve stenosis or atresia, atrial septal defect or ventricular septal defect. Many patients with Ebstein anomaly have an extra electrical conduction pathway in the heart. This can lead to times of abnormal fast heart rate called supraventricular tachycardia (this condition is known as Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome).

Ebstein anomaly can be very mild to very severe. Many patients with milder forms of Ebstein anomaly do not have symptoms and have normal oxygen saturations. When symptoms are not present until later in life, a diagnosis may be made when a heart murmur is heard.

Some babies and children have a blue color to their skin (cyanosis). This happens because of the flow of blood from the right atrium to the left atrium. Children may complain that their heart races, skips a beat, or just “beats funny.” They may tire more easily than other children or become short of breath. In teens and young adults, the sensation of "heart skipping" (palpitations) or fast heart rate, shortness of breath, and chest pain may be the first symptoms. Growth and development are normal in patients with Ebstein anomaly.

Severely affected babies are often critically ill at birth. They may have low oxygen saturations (cyanosis) and heart failure needing immediate intensive care.

A chest X-ray will be taken to look at the size of the heart, which may be larger than normal. Often, the diagnosis of Ebstein anomaly is suspected because of the large heart on chest X-ray.

An echocardiogram is used to diagnose Ebstein anomaly. It also helps identify any additional heart defects. This test allows the pediatric cardiologist (heart doctor) to determine the degree of valve displacement, and the severity of valve leakage (insufficiency) or valve narrowing (stenosis). It also helps see the size of the heart chambers, and if a PFO is present.

An electrocardiogram (ECG) records the heart's rhythm. If your child has complained about a racing heart and the answer is not found in this initial test, they may go home with a monitor. Your child may also have an exercise stress test done to better look at their heart function during activity. Some patients with abnormal heart rhythms may need more testing to identify and treat their heart rhythm problems.

Invasive diagnostic testing is not commonly performed today. Certain patients with Ebstein anomaly, may need cardiac catheterization to fully look at their cardiac anatomy and function.

Your child's pediatric cardiologist will discuss the treatment options appropriate for your child. Mild defects that do not cause symptoms often do not need medical or surgical treatment. Medical treatment is reserved for those children with congestive heart failure or abnormal heart rhythms.

Surgery may be needed for more moderate or severe defects. Surgical repair or replacement of the tricuspid valve and closure of the PFO or atrial septal defect may be recommended. Surgery might be needed for older children with moderate to severe congestive heart failure, significant heart enlargement, cyanosis, or abnormal clot formation.

Procedures in the cardiac cath lab may be used to help correct problems with fast heart rates. Medical therapy for heart failure or arrhythmias is used with planned surgery. In very severe forms of Ebstein anomaly, surgery may be needed in the newborn period. If this is needed, the treatment is more like that for children with single ventricle cardiac anomalies.

Children who have surgery do well.

Ebstein anomaly can be diagnosed at any age. People with the mildest form of the condition may not have any problems throughout their lives. But many people with Ebstein anomaly develop heart rhythm problems. These are more common as they age. Over time, limitations of physical activity are also common.

All Ebstein patients need lifelong follow up by congenital heart experts. Many Ebstein patients will need treatment for rhythm problems. Such rhythm problems can return, or new rhythm problems may occur. If surgery is needed, this should be done by congenital heart surgeons.

Learn more about the Adolescent and Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program

Last Updated 03/2025

Learn more about our editorial policy.