What is Tetralogy of Fallot?

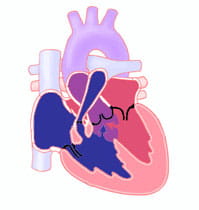

Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is a cardiac anomaly that refers to a combination of four related heart defects that commonly occur together. The four defects are:

- Ventricular septal defect (VSD)

- Overriding aorta − the aortic valve is enlarged and appears to arise from both the left and right ventricles instead of the left ventricle as in normal hearts

- Pulmonary stenosis− narrowing of the pulmonary valve and outflow tract or area below the valve that creates an obstruction (blockage) of blood flow from the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery

- Right ventricular hypertrophy − thickening of the muscular walls of the right ventricle, which occurs because the right ventricle is pumping at high pressure

A small percentage of children with tetralogy of Fallot may also have additional ventricular septal defects, an atrial septal defect (ASD) or abnormalities in the branching pattern of their coronary arteries. Some patients with tetralogy of Fallot have complete obstruction to flow from the right ventricle, or pulmonary atresia. Tetralogy of Fallot may be associated with chromosomal abnormalities, such as 22q11 deletion syndrome. It is important that this be identified so that other conditions can be treated.

The pulmonary stenosis and right ventricular outflow tract obstruction seen with tetralogy of Fallot usually limits blood flow to the lungs. When blood flow to the lungs is restricted, the combination of the ventricular septal defect and overriding aorta allows oxygen-poor blood ("blue") returning to the right atrium and right ventricle to be pumped out the aorta to the body.

This "shunting" of oxygen-poor blood from the right ventricle to the body results in a reduction in the arterial oxygen saturation so that babies appear cyanotic, or blue. The cyanosis occurs because oxygen-poor blood is darker and has a blue color, so that the lips and skin appear blue.

The extent of cyanosis is dependent on the amount of narrowing of the pulmonary valve and right ventricular outflow tract. A narrower outflow tract from the right ventricle is more restrictive to blood flow to the lungs, which in turn lowers the arterial oxygen level since more oxygen-poor blood is shunted from the right ventricle to the aorta.

Signs and Symptoms of Tetralogy of Fallot

Tetralogy of Fallot is most often diagnosed in the first few weeks of life due to either a loud murmur or cyanosis. Babies with tetralogy of Fallot usually have a patent ductus arteriosus at birth that provides additional blood flow to the lungs, so severe cyanosis is rare early after birth.

As the ductus arteriosus closes, which it typically will in the first days of life, cyanosis can develop or become more severe.

Rapid breathing in response to low oxygen levels and reduced pulmonary blood flow can occur. The heart murmur, which is commonly loud and harsh, is often absent in the first few days of life.

The arterial oxygen saturation of babies with tetralogy of Fallot can suddenly drop markedly. This phenomenon, called a "tetralogy spell," usually results from a sudden increased constriction of the outflow tract to the lungs so that pulmonary blood flow is further restricted. The lips and skin of babies who have a sudden decrease in arterial oxygen level will appear acutely more blue.

Children having a tetralogy spell will initially become extremely irritable in response to the critically low oxygen levels, and they may become sleepy or unresponsive if the severe cyanosis persists.

A tetralogy spell can sometimes be treated by comforting the infant and flexing the knees forward and upward. Most often, however, immediate medical attention is necessary.

Diagnosis of Tetralogy of Fallot

When a newborn with significant cyanosis is first seen, they are often placed on supplemental oxygen. The increased oxygen improves the child's oxygen levels in cases of lung disease, but breathing extra oxygen will have little effect on the oxygen levels of a child with tetralogy of Fallot.

Failure to respond to oxygen is often the first clue to suspect a cyanotic cardiac defect. Infants with tetralogy of Fallot can have normal oxygen levels if the pulmonary stenosis is mild (referred to as "pink" tetralogy of Fallot). In these children, the first clue to suggest a cardiac defect is detection of a loud murmur when the infant is examined.

Once congenital heart disease is suspected, echocardiography can rapidly and accurately demonstrate the four related defects characteristic of tetralogy of Fallot.

Cardiac catheterization is occasionally required to evaluate the size and distribution of the pulmonary arteries. Catheterization can also demonstrate whether patients have pulmonary blood flow supplied by an abnormal blood vessel from the aorta (aortopulmonary collateral).

Treatment for Tetralogy of Fallot

Once tetralogy of Fallot is diagnosed, the immediate management focuses on determining whether the child's oxygen levels are in a safe range.

If oxygen levels are critically low soon after birth, a prostaglandin infusion is usually initiated to keep the ductus arteriosus open, which will provide additional pulmonary blood flow and increase the child's oxygen level.

Infants who need a prostaglandin infusion to have adequate oxygen levels will usually require surgical intervention in the neonatal period. Infants with normal oxygen levels or only mild cyanosis are usually able to go home in the first week of life.

Complete repair is usually done electively when children are 4-6 months of age, as long as the oxygen levels remain adequate. Progressive or sudden decreases in oxygen saturation may prompt earlier corrective repair.

Surgical correction of the defect is always necessary. Occasionally, patients will require a surgical palliative procedure before the final correction.

Corrective repair of tetralogy of Fallot involves closure of the ventricular septal defect with a synthetic Dacron patch so that the blood can flow normally from the left ventricle to the aorta.

The narrowing of the pulmonary valve and right ventricular outflow tract is then augmented (enlarged) by a combination of cutting away (resecting) obstructive muscle tissue in the right ventricle and enlarging the outflow pathway with a patch.

In some babies, however, the coronary arteries will branch across the right ventricular outflow tract where the patch would normally be placed. In these babies, an incision in this area to place the patch would damage the coronary artery, so this cannot safely be done.

When this occurs, a hole is made in the front surface of the right ventricle (avoiding the coronary artery) and a conduit (tube) is sewn from the right ventricle to the bifurcation of the pulmonary arteries to provide unobstructed blood flow from the right ventricle to the lungs.

Treatment for Tetralogy of Fallot: Results

Survival of children with tetralogy of Fallot has improved dramatically. In the absence of additional risk factors, more than 95% of infants with tetralogy of Fallot successfully undergo surgery in the first year of life.

Surgical repair is more difficult when the pulmonary arteries are critically small or when the lung blood flow is supplied predominantly by aortopulmonary collaterals.

Most babies are fairly sick in the first few days after surgery, since the right ventricle is "stiff" from the previous hypertrophy (thickness) and because an incision is made into the muscle of the ventricle, making the muscle temporarily weaker.

This right ventricular dysfunction usually improves significantly in the days following surgery. Patients may also have rhythm problems after surgery.

An abnormally fast rhythm (called junctional tachycardia) may occur and may require treatment with medication or the use of a temporary pacemaker. This abnormal rhythm is usually temporary and the rhythm generally will return to normal as the right ventricle recovers.

Patients are also at risk for slow heart rates after surgery due to heart block. Heart block may be caused by injury to or inflammation of the conduction system in the heart. In many patients, the conduction improves and normal rhythm returns. Rarely, a permanent pacemaker may be necessary.

Since normal circulation is produced by the tetralogy of Fallot repair procedure, long-term cardiac function is usually excellent.

However, the repair usually leaves the child with a leaky (insufficient) pulmonary valve. In this situation, after the right ventricle pumps blood out to the pulmonary arteries, some of the blood will flow back into the right ventricle. This creates extra volume in the right ventricle forcing it to work harder and become dilated.

In a small percentage of children, this pulmonary insufficiency can lead to diminished function of the right ventricle. Symptoms of fatigue, especially with exercise, may develop. In these cases, replacement of the pulmonary valve is often recommended, typically in the teenage years or in young adulthood.

Patients who have had repair of tetralogy of Fallot can also redevelop a narrowing in the right ventricular outflow area or in the branch (left or right) pulmonary arteries, which will cause the right ventricle to pump at abnormally high pressures.

If these problems occur, additional surgical intervention to further widen the outflow tract or pulmonary arteries may be necessary. Narrowing of the pulmonary arteries can sometimes be treated without surgery, with balloon dilation of the vessels during cardiac catheterization.

Long-term follow up with a cardiologist to detect recurrent or new problems as early as possible is essential. Follow-up visits in the cardiology clinic usually consist of a physical examination, electrocardiogram and periodic echocardiography. In addition, these visits will also include occasional cardiac MRI scans, exercise stress tests and Holter evaluations as a child reaches the teenage and adult years.

Adult and Adolescent Management

Most adult patients with tetralogy of Fallot have had surgery to repair it in childhood. In some patients, the pulmonary valve is able to be preserved and they have no ongoing problems. Unfortunately, the majority do have issues; the most important one is leakage (regurgitation) of the pulmonary valve. This can enlarge the right heart chambers and lead to limitations in physical activity as well as heart rhythm abnormalities and occasionally sudden cardiac death.

Most patients with repaired tetralogy should have regular (usually annual) evaluation by a congenital heart expert. Pulmonary regurgitation can be treated with a tissue valve replacement. In many cases, pulmonary valves can be replaced using valves inserted through catheters (such as a Melody valve) rather than through a surgical procedure. This is usually a low-risk procedure that can allow the heart to shrink again and improve the patient's quality of life and life expectancy. These artificial pulmonary valves usually last many years in adult patients, but require expert surveillance.

Learn more about the Adolescent and Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program.