What is Coarctation of the Aorta?

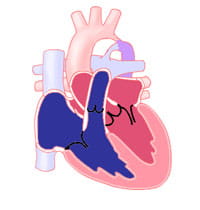

Coarctation of the aorta is a narrowing of the aorta. The aorta is the main blood vessel carrying oxygen-rich blood from the left ventricle of the heart to the rest of the body.

The coarctation occurs most often in a short piece of the aorta just beyond where the arteries to the head and arms take off. This is the area of the aorta where another blood vessel, called the ductus arteriosus, typically inserts.

The ductus arteriosus is a blood vessel that is normally present in a fetus. It has special tissue in its wall that causes it to close after birth, in the first hours or days of life. Coarctation may be caused by having extra ductal tissue.

In some babies with coarctation, the aortic arch prior to area of most significant narrowing may also be small (hypoplastic). Coarctation may also occur with other cardiac defects, typically involving the left side of the heart. The defects usually seen with coarctation are bicuspid aortic valve and ventricular septal defect. Coarctation may also be seen as a part of more complex, single ventricle heart defects. Coarctation of the aorta is common in some patients with genetic disorders, such as Turner's syndrome.

When a coarctation exists, the left ventricle must work harder to create a higher pressure than normal to force blood through the narrow part of the aorta to the lower part of the body.

If the narrowing is severe early in life, the ventricle may not be strong enough to do this extra work. This can lead to congestive heart failure or not enough blood flow to the organs of the body.

Diagnosis of Coarctation

Coarctation of the aorta is typically present from birth or shortly after birth. The age at which coarctation is found depends on the severity of the narrowing.

In about 25% of cases of isolated coarctation (without other associated cardiac defects), the narrowing is severe enough to cause symptoms in the first days of life. When the ductus arteriosus closes, the left ventricle must suddenly pump against much higher resistance to blood flow at the area of the coarctation. This can lead to heart failure and shock. Because these newborns are well until the ductus arteriosus closes, symptoms appear quickly. They are often severe.

In patients who do not develop heart failure as newborns, coarctation may not be found until the child is several years old. In these older patients, coarctation is often first thought of because of a heart murmur or high blood pressure.

Coarctation is also considered when the doctor is unable to feel pulses in a child’s legs. High blood pressure in the arms (but not the legs) is often present. A heart murmur is usually present. It may be loudest in the back where the aorta is located.

The diagnosis of coarctation is confirmed with echocardiography. This can look at the anatomy of the aorta. It can also check for other cardiac anomalies that may be present and give important information about the function of the heart. Sometimes other tests, such as a cardiac MRI or CT scan, may be used to look at the aorta and coarctation in more detail prior to intervention.

Coarctation may also be diagnosed on fetal echocardiograms. It is one of the cardiac defects that may be found on screening ultrasounds. Early diagnosis allows for prompt intervention at the time of birth. However, while the ductus arteriosus is open in utero it can be unclear in some patients if there is a risk of a coarctation forming. Some infants may need to be observed closely after birth as the ductus arteriosus closes to detect if there is coarctation.

Planning to deliver an infant at a hospital capable of newborn resuscitation is important in improving the chances for a good outcome.

Learn more about our Fetal Heart Program.

Managing Coarctation

In a critically ill newborn who comes into the hospital after the ductus arteriosus closes and there is a severe coarctation, the goals are to improve ventricular function and restore blood flow to the lower body. A continuous intravenous medication, prostaglandin (PGE-1), is used to open the ductus arteriosus. This allows blood flow to the body beyond the coarctation. Often other intravenous (IV) medicines may also be needed to help the function of the heart. Many babies need to be placed on a ventilator before surgery.

If the baby has symptoms of a coarctation, surgery is done on an urgent basis.

If there is a high suspicion of a coarctation prior to delivery, the PGE-1 medication can be started soon after birth to prevent the ductus arteriosus from closing. In this case, surgery would be done to repair the coarctation prior to discharge home from the hospital.

There are a few surgical techniques to repair coarctation. The most common repair involves resection (removal) of the narrowed area with anastomosis (reconnection) of the two ends to each other. Sometimes the removal of tissue must be extended further into the aortic arch if there is a longer piece of narrowing. In another method, the narrowing may be opened with a patch or a portion of an artery may be used as a flap to expand the area (called a subclavian flap aortoplasty).

To repair coarctation surgically, clamps must be placed on the aorta. This will quickly interrupt blood flow to areas supplied by blood vessels from the aorta. Complications of surgery include damage to organs such as the kidneys or the spinal cord, but these are not common in children.

Because older children may have minimal symptoms, coarctation repair is typically planned electively. Surgical repair is usually done with resection of the narrowed piece and end-to-end reconnection.

In older children who are closer to adult size, transcatheter therapy is the first-line therapy. It offers the ability to use a balloon or stent to dilate (make the area bigger) the area of narrowing without needing surgery. In children who are still growing, the placement of a stent means that additional catheterization procedures are likely to be needed in the future as the stents cannot grow with them.

Results of Treatment

Return or re-occurrence of coarctation at the site of surgical or balloon treatment is possible. This may even happen years after surgery. The rate of restenosis is highest among newborns. This happens in 10-20% of patients. The rate of recurrent coarctation after surgical repair decreases in older children. The rate is close to zero by age 3 years. Some patients with recurrent coarctation may need repeat surgery. Most cases can be managed with balloon dilation of the area of narrowing or stenting.

Less commonly, aneurysms or areas of dilation can form at the site of repair or in the aorta. These can often be treated with stents placed via transcatheter therapy.

Another concern after coarctation repair is hypertension (high blood pressure). While this is rarely seen in infants, most older children have unusually high blood pressure right after surgery. This is treated with intravenous medicines while in the hospital. Children will often be sent home with medicine to take by mouth to treat high blood pressure.

Blood pressure will return to normal in many children over time (allowing medicine to be stopped). Long-term or late hypertension may occur in some patients, who then need long-term treatment.

Lifelong follow-up with a cardiologist is important for children after coarctation treatment to diagnose late problems of restenosis or high blood pressure. Follow-up visits include a physical exam with blood pressure measurements in both the arms and legs. Periodic echocardiograms are also needed. In older and larger patients, cardiac MRI or CT scans done to get a better look at the repaired aorta. Long-term cardiology follow-up is also important for any additional heart problems.

We expect patients with a repaired aortic coarctation to do well. But additional treatment may be needed to protect their long-term health.

Learn more about the Adolescent and Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program.